Bristows’ Richard Pinckney discusses life in patent litigation and why science marries perfectly with the law

When one imagines the career journey of an intellectual property (IP) lawyer, the common expectation might be that they always knew law was their calling. For Richard Pinckney, a partner at Bristows, that path was more of an evolution – a journey where science and legal practice came together to form a fulfilling career. I sat down with Pinckney, who opened up about how he transitioned from engineering to law, sharing his reflections on why IP litigation is magnet for young scientists.

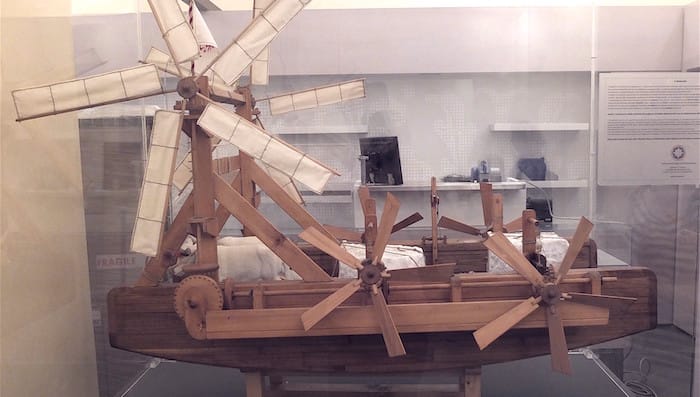

Pinckney’s career journey began with an academic background in engineering. “I studied engineering science,” he recalls, “and I had to think about not only what I wanted to do as a job but what I wanted to do as a career.” At that stage, he hadn’t even considered law as an option until a friend suggested that it might suit his personality and interests. “The idea of being a solicitor or lawyer hadn’t really occurred to me,” Pinckney admits. “But I looked into it and discovered this whole field of law called intellectual property, which I knew nothing about before, and quickly realised that I would enjoy it.”

This realisation led him to pursue a vacation scheme at Bristows, where he got his first real taste of what a career in IP law could look like. “Not every career lets you try it out before you do it,” he reflects. “I sat in intellectual property litigation during my vac scheme, and it definitely ticked the box of letting me engage with the science, as well as pushing me and challenging me in new ways.” The experience confirmed that IP litigation would allow him to engage with science in ways that were intellectually fulfilling.

The world of IP, and particularly patent litigation, allowed Pinckney to blend his engineering expertise with legal problem-solving. He explains that it gave him the chance to engage with science while simultaneously tackling the legal challenges surrounding it. This combination—melding the technical with the legal—was exactly what made IP law appealing to Pinckney. “I didn’t want to specialise too soon,” he says. “I wanted a career that had an established path and allowed me to become an expert in a field quickly. I was drawn to a career where someone would seek my advice as an expert, which is why law, and particularly patent litigation, appealed to me.”

Why did your friend suggest that you’d be a good fit for the law? I ask. “I think they saw that I wasn’t the type of person to sit in a corner and tinker with things all day,” he replies candidly. “I was a bit more outgoing than that. They believed I would excel in a career that not only required problem-solving skills and intelligence but also allowed me to interact with people and engage with them on a more social level.”

A significant part of Pinckney’s story is his long tenure at Bristows, a firm known for its expertise in IP and technology law. Unlike many legal professionals who hop between firms in search of the right fit, Pinckney found his home at Bristows early in his career. “Bristows doesn’t have a chargeable hour target,” he emphasises. “We motivate our fee earners by doing really good quality work, respecting each other, and wanting to demonstrate effective advice.” In a world where the billable hour is often king, he tells me that Bristows has created an environment that fosters quality over quantity, attracting talented lawyers who are driven by the intellectual demands of their work rather than the pressures of clocking hours.

Reflecting on what initially drew him to the firm, Pinckney says, “Bristows is one of the best places to do patent litigation. It has the best clients, does top-quality work, and has some of the best lawyers in the field. But what really attracted me was that isn’t a big, faceless firm where I would be just another number in the machine.” He continues, “So, if I answer the question of why I’m still here, what reassures me is that all the reasons I joined Bristows remain true.”

“Bristows is still one of the top firms for patent litigation, consistently ranked at the highest levels,” he continued. “The people I work with are incredibly smart and continue to challenge me. We have great clients, and the work we do is always of the highest quality.”

One of the most intriguing aspects of Pinckney’s work is the nature of IP disputes themselves. Patent litigation is, by its very nature, a marriage of science and law. For Pinckney, this is where the challenge and the reward of the job lie. “I normally have two or three ongoing projects or litigations at the same time, always in the field of technology, often focused on patents,” he shares. His current work often involves telecommunications companies and patents essential to the development and sale of cutting-edge products. A recent case he’s been involved in revolves around third and fourth-generation (3G and 4G) telecommunications technologies, with disputes over patent infringement, patent validity and appropriate licensing terms.

“We’re working with a client in the telecommunications field who owns a large portfolio of patents related to 3G and 4G technologies,” Pinckney explains. “They’ve asserted those patent rights against two companies that manufacture and sell mobile phones. The work involves both proving that our client’s patents are valid and figuring out how much the defendants should pay to use that technology.”

In these cases, Pinckney and his team must prove that their client’s patent rights are valid, establishing that they are novel inventions deserving of protection. At the same time, they must argue that these patents have been infringed upon, often by well-known manufacturers of mobile devices. In Pinckney’s view, this combination of highly technical legal and commercial questions is what makes patent litigation so fascinating.

With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), Pinckney’s practice area is on the cusp of even greater change. Generative AI is poised to impact the way intellectual property is protected and commercialised. When asked about AI’s role in IP law, Pinckney acknowledged that while AI will certainly streamline processes, it won’t replace the need for human judgement in complex legal matters.

“AI will make our jobs easier and overall will save our clients money, but the vast majority of the work we do will not be able to be done by AI,” he explains. The role of AI in patent law goes beyond automation; it also raises new legal questions about whether AI can be considered an inventor and whether its creations can be patented. “There are fascinating questions like, ‘Can an AI algorithm be the inventor of a patent?’” Pinckney muses. “These kinds of legal questions will become more frequent as AI continues to evolve.”

Moreover, Pinckney’s background in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) has equipped him with a unique perspective that makes him well-suited to navigate these technological shifts. As the legal profession increasingly intersects with advancements in science and technology, lawyers like Pinckney, who possess both technical and legal expertise, will be invaluable.

When asked why STEM students should consider a career in law, Pinckney highlighted the logical nature of both fields. “Law is also logical,” he notes. “There are rules you follow, but you also have to exercise judgement.” For STEM graduates who enjoy the structured, problem-solving aspects of science and engineering, he emphasises that a legal career can offer similar intellectual rewards, especially in fields like patent litigation where the subject matter directly overlaps with scientific and technological innovation.

Drawing the interview to a close, Pinckney offers a piece of advice that, while simple, is perhaps the most important lesson for anyone considering a career in law — or any field, for that matter. “Focus on what you enjoy,” he urges. “If you enjoy it, it’s so much easier.” He emphasises the importance of aligning your career with your passions, explaining that it not only makes the work more enjoyable but also motivates you to engage fully with it. “Once you figure out what it is that you enjoy, throw yourself into it. Don’t just sit back and watch life go by — actively engage with your career.”

About Legal Cheek Careers posts.